Let's stick to what we know

Investors have found it difficult to resist the temptation to become armchair generals in response to the recent flurry of geopolitical volatility. I have some sympathy for that. Political experts told us that Mr. Trump would mark the beginning of a new U.S. isolationism, and even speculated about the emergence of a new Monroe doctrine. The president's "America First" discourse, the statement that NATO is obsolete, and the rapprochement to Russia were all pivots watched ominously by other world leaders, especially in continental Europe.

This story, however, increasingly feels like ancient history.

The decision to re-engage in the Syrian conflict—which had hitherto been left in the hands of Turkey and Russia—marks a big shift, and also has also raised questions about just how chummy Mr. Trump and Putin are. The strike on the Syrian airbase was carried out in the wake of the apparently Assad-approved chemical attack, but we can't really be sure that was the only reason the U.S. decided to stick its nose back into the Middle East. The decision to drop "the MOAB" in Afghanistan suggests that the role of the world's policeman is one that Mr. Trump is happy to assume. This is to say, provided it helps diverting attention from challenges closer to home, of which there have been plenty. Finally, the new U.S. administration is being faced with an increasingly bold and risky North Korea. As a result Mr. Trump has decided to put the country on notice by sending a group of warships, apparently joined by the Japanese navy , to send a signal to Pyongyang that further tests of ICBMs will not be tolerated.

I could spend hours in the pub discussing these exciting changes in the global geopolitical landscape, but I am not sure it would do my investment or market analysis any good. I am also loath to accept the idea of a causal link between geopolitical volatility and markets' gyrations. After all, the advice to "sell everything" on the back of geopolitical changes does not have a good track record. Indeed, that hissing sound you're hearing isn't only U.S. equities losing momentum. It is also the collective sigh of relief from leaders in the developed world in response to signs that U.S. is, once again, willing to solve the problems they don't want to, or can't, deal with. One man's political uncertainty can quickly become another's certainty.

What do we know?

We know that U.S. equities have lost their mojo recently. Going by weekly closes, the S&P 500 peaked in the first week of March, and has since declined 2.3%. This has left believers in the reflation trade frustrated, but it hasn't provided much fodder for the bears. Spoos have eased lower rather than collapsed, undoubtedly to the disappointment of the many bear guilds hoping for a collapse. The first chart below show that the loss of momentum has done clear damage to trailing returns in line with my model for the S&P 500 using HYG, gold and the CRB. This framework is a decent proxy for the fading boost to risk assets from the reflation trade. The second chart shows breadth, which is now negative. This is no guarantee of further weakness, but it has been tough to short the market whenever this indicator has been above zero.

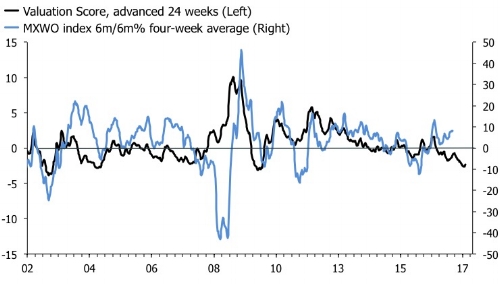

The upshot for investors, so far, is that Eurozone and EM equities have outperformed. This has led a growing number of equity strategists to hit the tape, proclaiming that overweight everything other than the U.S. is the new black. I am all for relative performance trades but as I have tried to explain, I struggle with the idea that equities outside the U.S. are outright cheap, especially in Europe. The second chart below shows trailing returns for the MSCI World against my forward-looking valuation score based on technicals and fundamentals. The message is clear; this is not a good time to buy global equity beta.

We also know that the bond market is sending a strong signal not to chase the reflation trade. The curve in the U.S. has flattened, rewarding those of us who have been accumulating benchmark fixed income in Q1 as the reflation hype was reaching its zenith. The first chart below shows the 2s5s, which I think is a more important for investors to look at than the 2s10s. If the Fed has to punch it, I think a divergence between sharply higher 2-year yields and falling 5-year yields would be the key bellwether to watch. This is to say, if this spread steepens in response to an aggressive Fed, we will know that everything I have been saying so far is wrong. But if it doesn't, we'll know that we're entering a more garden-variety late-cycle stage in the U.S. economy. In addition, the second chart below shows my model for the U.S. 10-year future, which also continues to indicate upside risks for bond prices.

Finally, while headline macroeconomic leading indices have turned up, they are not pointing to accelerating growth. The first chart below shows that my global LEI diffusion index has turned up, but it doesn't indicate that the current tepid momentum in global industrial output of about 1.5% year-over-year is about to improve anytime soon. To be fair, this message is decidedly more downbeat than if we look exclusively at manufacturing survey data. These quintessential "soft data" point to much stronger underlying momentum. We need hard data for a few more months, and full revisions for Q1, to see what is really going on. In addition, macroeconomic data are now no longer surprising to the upside. The second chart below shows that macroeconomic surprise indices in the U.S., the Eurozone and emerging markets have rolled over. That doesn't necessarily mean anything for the economy, but it does add further evidence that the reflation trade probably has soared too high too fast since Mr. Trump came to power.

The story outlined above is pretty much the same as the one I have been telling in the past few months. As a result I have made minimal changes to the portfolio recently, which has been a good decision. Confirmation bias is a dangerous thing, though, and it is always a good idea to think about what you're missing. A sharp reversal in the bond market towards a steeper curve would be the clearest sign that I am wrong. I would expect significant underperformance in such a scenario. Interestingly, a more benign interpretation of recent geopolitical uncertainty is probably the key risk in this respect. A resurgent U.S. in global politics once again relying on, and using, its key allies is also arguably a U.S. which doesn't care much about a stronger dollar and bilateral trade deficits. As Mr. Trump poignantly put it on Twitter. Why on earth should he single China out for being a currency manipulator, or for cheating in trade(?), when Beijing is helping to solve the problem in North Korea. Politicians in Germany might want to consider what they can do to receive a similar pass. If this story gets more traction, it is likely a theme that financial markets will play via a stronger dollar and higher U.S. yields. For now though, a gentle sell-off in equities probably is exactly what I need to shine, and that is exactly what I am getting. Sometimes the best strategy is to act on what you know.