The Carry Trade and the Global Monetary Credit Transmission

Daedalus warned his son not to fly too close to the sun, nor too close to the sea. Overcome by the giddiness that flying lent him, Icarus soared through the sky curiously, but in the process he came too close to the sun, which melted the wax. Icarus kept flapping his wings but soon realized that he had no feathers left and that he was only flapping his bare arms. And so, Icarus fell into the sea. - Wikipedia entry on Icarus

Whether it is merely temporary or a sign of something more durable it is hard to escape the fact that as the discourse on green shoots and second derivatives linger we might be entering a new leg of this crisis. Thus, there should be no mistake. We are very much still stuck in the mire and especially so in the context of the so-called developed OECD economies where it is difficult to see where any speedy recovery is going to come from. On the other hand the world is not made up entirely by the OECD edifice and it is exactly the potential for an asymmetric "recovery" and how global monetary policy might serve to transmit such a recovery which is the topic of this entry. In order to frame the discussion, it is worthwhile to go back to before the crisis where, most notably, the low interest rate environment in Japan was driving carry trading activity across the world with Australia, New Zealand, the Eurozone, the US as notable targets in the developed world edifice where also of course emerging markets were in the spotlight. Whether there are similarities with such historical flashbacks can be debated; but what is abundantly clear is that conditional on the return of some variant of an environment conductive to the carry trade something has also changed.

This change is most clearly expressed through the process by which the US Fed's credible commitment to maintain low rates may become the driving force for a search for yield and return (carry trade) in key emerging economies. In that light, my good friend Edward Hugh recently authored two extraordinarily important pieces and although it is hardly news that I plug Edward at this space I highly recommend you to have a look at these two. Nay, it is imperative that you read them.

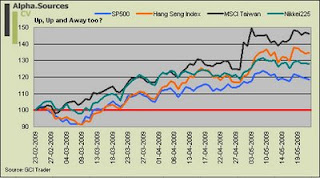

The main thrust of the story is that after having observed green shoots throughout since February the carry trade wheel appears to be revving up again. Volatility have come down, risky assets have flown, money market rates in the G3 are beginning to behave, and reports have even come in that a seasoned carry trade veteran Miss Watanabe is once again dipping her toe although people close to the data also suggest that a lot of the effect from Miss Watanabe is clouded by Japanese corporates playing with transfer pricing.

[click on graphs for better viewing]

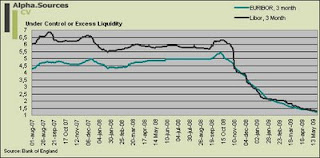

But, as noted, this time there is a twist. Sure, the BOJ is still running an almost open shop with respect to the provision of funding to play the game but relative to the carry trade of old days, something has changed. Now, it is not the only the BOJ anymore but also the BOE, to a lesser extent the ECB, and most importantly the Fed who are forced to commit to very low levels of nominal interest rates in order to fight off deflation as well as to commit to the support of the restoration of a financial system which has been mortally wounded during the evolving crisis. In a world where uncertainty is high this is a prerequisite to avoid disaster, but in a world where sentiment suddenly shifts to the better it potentially becomes the underpinning factor for what some have dubbed the mother of all carry trades. It is of course this which we have been observing more than passing evidence of in the past weeks.

In a global macroeconomic context, this all goes back to the discussion of re-balancing and decoupling. In the most recent print edition The Economist calls it decoupling 2.0 and although I never liked the idea of decoupling as it was traditionally narrated with Europe or perhaps China taking over as the global supplier of net capacity (demand) it was also always going to be a very true narrative. To put it in other terms; the world decoupled a long time ago and it has long been clear that big emerging economies would rise to the scene to command a much larger relative position.

Besides this common ground, I have mainly had two gripes with the narrative. Firstly, the original idea that Europe and Japan would rise to the occasion to take over from the US was a mirage masked by the simple fact that the Fed reacted more quickly and swiftly to the incoming storm. Secondly, I have also been skeptical about the idea of China (and Russia even) providing demand through a more liberal policy towards the management of its capital account and currency. Essentially, Goldman Sachs' old conceptualization of the BRICs should be allowed to move into the eternal dust bin not only because there is a fundamental difference between China/Russia and Brazil/India, but also because the emerging market edifice is much more diverse and important to be reduced to the whims of the punch line department at the world's biggest and arguably best investment bank.

With these points on the table it is of course worthwhile to ask whether investors and other market participants are responding to this new narrative of vibrant growth in emerging markets and subsequent carry trade opportunities.

Even a modest glance over the recent news bulletins suggests almost a feeding frenzy as investors and their advisors scramble to exploit whatever window of opportunity that may have opened to make some easy money in an otherwise extraordinarily difficult environment. One notable example was in the context of the CEE economies where Deutche Bank recently suggested that investors borrow in Euros to buy the Ruble and the Forint. Of course, there are carry trades and then there is; well Russian roulette, and of all the potential punts out there this one would seem, to me, the equivalent of a trip to Las Vegas, playing on horses or another derivative of gambling. Apart from DB, Barclays have also picked up the baton with analyst Andrea Kiguel providing the main points that the Brazilian Real and Turkish Lira be the preferred targets of choice;

Brazil’s real, South Africa’s rand and Turkey’s lira offer the “largest upside” as investors return to the so-called carry trade, Barclays Plc said. A global pickup in investor demand for higher-yielding assets and signs the worst of the global recession is over “bode very well for the comeback of the emerging-market carry trade,” analysts including Andrea Kiguel in New York wrote in a report. The carry trade refers to the practice where investors borrow funds in a country with lower interest rates and then invest the money in nations where returns are higher.

Brazil’s real has gained 18 percent in the past three months against the U.S. dollar while Turkey’s lira has advanced 10 percent. South Africa’s rand is up 22 percent, the best performing emerging-market currency in the past three months. “As the decline of global risk aversion gives way to the re-pricing of U.S. dollar, we see potential for emerging-market foreign exchange to continue rallying,” analysts including Andrea Kiguel in New York wrote in a report.

The American Banks want to play ball too and emphasising the unusual and lingering low interest rate environment in Europe, Japan, and the US; JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs are hailing all systems go.

The carry trade is making a comeback after its longest losing streak in three decades.

Stimulus plans and near-zero interest rates in developed economies are boosting investor confidence in emerging markets and commodity-rich nations with interest rates as much as 12.9 percentage points higher. Using dollars, euros and yen to buy the currencies of Brazil, Hungary, Indonesia, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia earned 8 percent from March 20 to April 10, that trade’s biggest three-week gain since at least 1999, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Insight Investment Management and Fischer Francis Trees & Watts have begun recommending carry trades, which lost favor last year as the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression drove investors to the relative safety of Treasuries. Now efforts to end the first global recession since World War II are sending money into stocks, emerging markets and commodities.

Speaking a language most investors can understand Bloomberg reports that a composite index constructed by ABN Ambro where the Euro, Yen, and USD are used to buy Turkish Lira, Brazilian Real, the Forint etc has so far earned an annualized 196 percent from March 2 to April 10. Such kind of rapid reversal of fundamentals can only be underpinned by a very strong dose of positive sentiment as the one we have been witnessing with all the talk about green shoots and second derivatives. As Macro Man points out the most recent survey on Global Funds Managers from Bank of America and Merril Lynch sported the biggest degree of optimism since 2004 and, naturally, a substantial re-allocation of assets towards emerging markets.

Now, this is of course all well and good but the underlying economic dynamics here are not as straight forward as they may seem. There are particularly two issues worth noting.

On the one hand there is the simple issue of where all the liquidity provided by the BOJ, the ECB and the Fed is going. Only recently, the vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Donald Kohn pointed out that after getting a one trillion dollar boost from the Fed's purchase of treasuries and asset backed securities (most notably the MBS) the economy appeared to be on the mend. Leaving aside the question of whether the economy is actually on the mend or not the more fundamental question is the extent to which the Fed, the ECB and the BOJ can govern where exactly this "boost" is going and, of course, subject to what leverage multiple. This, I think, was what made Paul Krugman ever so timidly to venture the idea the perhaps some form of buy American/protectionism wasn't as bad as it was meant out to be. In a European context we can ask a similar question about whether all the liquidity provided by the ECB will simply move into the CEE to play the carry there and consequently further exacerbate the imbalances which have not been unwound yet.

On the other hand there is the receiving end where some emerging markets are already reeling under the prospects of sucking up the inflows. The first proverbial shot across the bow was fired by Henrique Meirelles who is in charge of the Brazilian central bank. Recently, he consequently pointed out that the central bank is standing ready to increase the purchases of USD in order to stem the unduly appreciation of the Real on the back of carry trade optimism and a resurgence of the upward trend in commodities which is a core driving force in the Brazilian case. But this runs much deeper than Meirelles recent comments. Going back to the last time, before the crisis, many emerging markets and commodity linked economies also squirmed under the pressure of inflows. Of course and undoubtedly much to the chagrin of many central bankers, raising rates to quell the inevitable inflation which comes on the back of hot money inflows only serves to worsen the problem. Thus, and with a number of central banks stuck at near 0 % in nominal interest rate, raising rates only intensifies the pressure. This was abundantly clear in economies such as Brazil, India, New Zealand, Australia, and most importantly in the CEE where many economies actually depegged with respect to the Euro because it was believed that the carry flows would lead to nominal appreciation which would choke off the inflation. The most ardent example of an attempt to halt the carry pressure was of course Thailand where capital controls on inflows were installed, not in order to to stem an outflow as originally described in the literature, but rather to avoid to much money coming in.

The key to understand this process is the nature of global monetary policy and the so-called credit channel. This is one of the reasons why I demand that you read Edward's posts linked above, but you could also go right to the source in the form of a paper by Danish economist Carsten Valgreen as well as my own account of said paper. The point is simply the extent to which economies can loose control over monetary policy and what this means. There is ample evidence I think that in a world where interest rate differentials of the current magnitude represent an inbuilt part of the edifice, there exist notable externalities from monetary policy. One aspect of this is created by the fact that some central banks basically have committed to a prolonged period of quantitative easing and another aspect is created by the fact that as the crisis ripples through, the world will be saddled with more economies than before dependent on exports to grow. These two facts taken together suggest that the pressure on those brave souls out there willing to stand up and run a deficit will also face what I have come to call a "turret ride" since when times are good the inflows may seem excessive only to retreat if the mood turns sour. As noted, following traditional convention hot money inflows can create investment bubbles and inflationary pressures (if you don't have the capacity) and the answer would be to raise rates, but if the low risk environment persists such policy measures will only intensify the pressure. I think that this aspect of the global economy is very important to take aboard.

Into the Light with Wings of Wax?

This may of course be much ado about nothing since in the current environment wreckers of havoc to the carry trade and any other kind of risk prone activity potentially lies around every corner. In this sense I agree with people closer to the market than myself. However, it is still worth paying attention to the way markets and investors are reacting and then to think about the consequences of the joint commitment by the big central banks to keep rates low. Clearly, such commitments are always subject to withdrawal if and when the respective central banks see it fit to suck back the liquidity, but so far that point is far into the horizon. This means that we are about to see just how much capacity there is to absorb the carry flows and where the money ultimately will flow. Some investors will certainly be flying equipped only with similar wings as Icarus while some again will be sporting a set of more durable wings. Whatever the future days and weeks will bring, I for one think it is fascinating to watch.