Is global inflation (re)accelerating?

This is the question everyone wants an answer to after another week where bonds have been beaten to a pulp, a trend which is now starting to bleed into equities. More specifically, the real question is whether US inflation is accelerating? It is too soon to tell, and for the record, we don’t think so. But for now, markets are being fed with headline macro data signalling that the US economy is more resilient than previously anticipated, as well as vulnerable to upside inflation risks. As a result, investors have kept buying the dollar and selling treasuries at the start of 2025. The latter, in turn, has spilled over into indiscriminate selling of bonds in other jurisdictions.

This global dimension of the bond market rout is partly justified by the fact that any upside risks to US inflation has an international component through three routes. First, the US is the global biggest economy, and a key source of global demand for goods and services, so it makes sense that signs of relative strength feeds into international markets, interest rate and inflation expectations. Secondly, to the extent that fears of stickier inflation in the US is driven by expectations of Mr. Trump’s trade policies, or the attempt by the outgoing administration to limit the movement of Russian oil to third countries before being re-integrated into global supply chain, this should lift global inflation expectations. That said, significant uncertainty still exists over just how inflationary a trade war will be, given that its net inflationary impact in any given region depends on how fiscal and monetary policy responds. Thirdly, a sustained strengthening of the US dollar lifts inflation expectations in non-US economies via the FX channel, though also here, economists disagree on how strong this link is and, by extension, how serious monetary policymakers should take it. This is particularly the case in the UK and Eurozone. By contrast, the inflation/FX channel in emerging markets is more generally agreed to be important. China, for its part, command a unique role here given that it manages its currency, and that it presently doesn’t have a domestic inflation problem. On the contrary, Chinese inflation indicators remain weak and borderline deflationary, which is partly why Chinese government bonds have been rallying recently.

Anyway, back to the question. Is global inflation (re)accelerating? No, but it is perhaps not falling as quickly as markets thought a few months ago, which goes some way to explain the re-pricing in bonds. The charts below update the global inflation indicators I like to track as a broad overview. The first shows that DM headline inflation increased in October and November, and by the end of this week, we’ll likely learn that it climbed a bit further in December. In the core, meanwhile, the story is mainly one of stabilisation. US core inflation has been locked slightly below 3.5% since May, a story similar to the UK, though core inflation here has been more volatile. In the euro area, the core HICP has been rising by just under 3% year-over-year since over the same period, falling fractionally in the past few months, to around 2.7%. The second chart below shows that the 3m/3m 2nd derivative of DM core inflation jumped to around zero at the end of 2024, which is a quantitative way of saying that core inflation is now no longer falling.

Looking past the actual CPI data, my survey-based global leading indicators for inflation have increased slightly in both goods and services, but once smoothed, the trends in either aren’t really shifting decisively higher just yet. Similarly, the Chinese goods PPI and global commodity prices—two bellwethers for global inflation—aren’t exactly screaming upside inflation risks either.

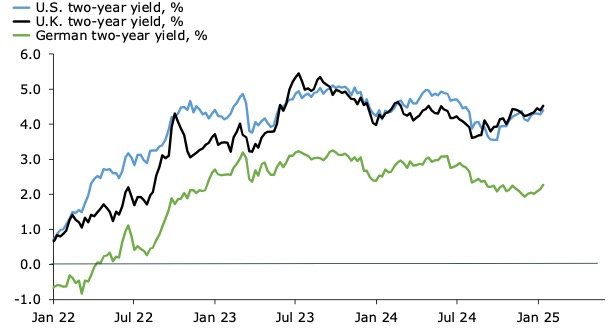

So, what’s the fuss in bond markets all about? In a nutshell, the combination of core inflation stabilising at 2.7-to-3.5% and 2% inflation targets is a problem for DM central banks. It means that they won’t be able to lower interest rates as quickly as they had hoped, and markets have been anticipating, which in turn is driving two responses in bond markets. The front-end is being priced higher, and because this is linked to the idea of “higher-for-longer”, the long-end has bear-steepened the curve as markets are looking for an equilibrium with a positively-sloped yield curve at a “permanently” higher short-term interest rate. Time will tell whether the data eventually will push bonds towards a more benign equilibrium. It will come to no surprise to those who have been following my analysis of inflation in a post-Covid world that the tension between a soft landing in the global economy, and a perfect landing for inflation at 2%, is driving volatility in bond markets and interest rate expectations.

The upshot for bond bulls, apart from relatively benign global inflation leading indicators shown above, is that the bond yield charts aren’t really looking that scary, yet. On the front end, the downtrend in yields in the US and the UK from the highs in 2023 is still intact, just. And in the Eurozone, all bond markets are now saying is that the ECB’s terminal rate will be slightly above 2%, which wouldn’t exactly be a terrible outcome given current inflation dynamics and an unemployment rate still at a record low. On the 10-year, yields in the US and the UK are now both at the very high end of their ranges since the middle of 2023. A sustained break above 5% in either of these would be a signal of more significant shift. In the Eurozone, the message from the 10-year bund is more moderate, in line with the signal from two-year yields that the ECB will not push rates below 2% this year as was otherwise expected by markets towards the end of 2024. So, to repeat, bonds are, in my view, not pricing-in a (re)acceleration in inflation as much as they’re pricing-in a slower-than-anticipated decline, for now.