The Big Short on Volatility

Two investment themes in particular, since 2008, have been predominant in my view and the continuation or unravelling of both hold the key to successful asset allocation in the next 3-5 years. The first is the suppression of volatility on the back of aggressive and ongoing central bank intervention. The second is the hunt for yield characterised by two key currents. Firstly, investors have been pushed far out the risk spectrum (often reluctantly). Secondly, we have seen bonds and stocks appreciate and depreciate together which has put into question core tenets of traditional portfolio allocation.

The overarching investment conclusion from the points above is obvious. The focus, hysteria and obsession around central bank policy will continue for it is increasingly clear that politicians and financial markets have collectively put all their (and our) eggs in one basket. If central bankers were to secretly convene in a room to decide applying a dose of Volcker’s medicine the fallout would be devastating. Such hawkish coordination may seem a ludicrous proposition, but the margin between blunders, policy errors and deliberate policy changes is a blurred one. Having your success as investor depend on central bank policy may seem a merciful alternative to the chaos that prevailed first in 2008 with the global financial system on the brink of collapse and then later in 2012 with sovereign defaults and break-up fears in the eurozone. However, if central bank intervention and economic volatility are joined at the hip then it suddenly looks like much more like a Faustian deal.

Whether it be the Fed’s exit policy, the ECB’s non-action policy or the BOJ’s surrender to fiscal dominance, investors not only need to hope that each of them get the balance right, but also that they are allowed time to adjust their portfolios to any changes. But herein also lies the problem. The era of central banks as eminences grises is over and it is not clear to me that their new found power and freedom to deploy their vast arsenal of theoretical and practical tools will end well.

Wanted: A dynamic strategy to trade volatility

The introduction above is a suitable synopsis I hope for introducing one of the most interesting investment strategy pieces that I have read in a while [1]. Written by Christopher A Cole, an investment manager, it operationalises a number of the themes above in a way that it is worthwhile for investors to think about in my view. As a founding partner of Artemis Capital Management, a hedge fund specialising in giving investors exposure to volatility, Cole’s piece could simply be seen as marketing material. But discarding his arguments on this background would be a mistake.

Indeed, Cole is predictably vague on the actual implementation of an active volatility trading strategy [2] more so that he lays out a conceptual framework. The main point in a nutshell is the following. Volatility is an asset class in itself and should be traded accordingly. The best way to look at volatility in this perspective is to trade its term structure and to recognize that the market price of risk differs across maturities captured exactly in different prices for options at different points in time.

This gives rise to the notion of known unknowns and unknown unknowns taken, as it were, from none other than Donald Rumsfeld. This concept was introduced in earlier versions of this argument presented by Artemis and Cole, the key is the following.

Volatility trading is about putting a price on known unknowns and unknown unknowns. (…) The known unknown crash is predictable in retrospect, but the unknown unknown crash is unpredictable even in retrospect; its cause is never truly understood.

This will appear vague to many investors, but the main take-away in my view is to have a dynamic strategy towards trading volatility. Most investors tend to be either long or short (flat) volatility relative to a benchmark long risk position. As a way forward from this benchmark position Cole introduces the concept of Crisis Alpha employed by Artemis to give exposure to volatility. The particulars are unclear, but the main point is valid I think.

My emphasis

Many investors tend to think about volatility only in terms of direction: long or short volatility. Hence, within this limited view, there are either tail risk funds that lose money waiting for a black swan that may never appear or anti-fragile short volatility funds that are a 100-year flood away from the inevitable blow-up. Crisis alpha, although skewed toward the long side, takes a balanced path, relying on relative value volatility trading. This approach is conceptually similar to trading fixed income across the yield curve.

While this may not be a crucial innovation for seasoned volatility traders, such a perspective on volatility greatly enhances the way traditional long-only and long/short managers look at the concept of hedging. The obvious question that imposes itself after accepting this notion is then how to implement such a volatility trading strategy. I hope to have something substantial to say about this later, but looking at volatility through the lens of a term structure already allows for a much richer and powerful perspective relative to being either long or short volatility. After all, looking at a curve, measuring steepness, flatness etc relative to its history are all tried and tested means to knit together asset allocation strategies in other markets. In many ways, this perspective on volatility could go a long way to democratize volatility as an asset class for investors otherwise not familiar with or inclined to step in the often highly quantitative world of volatility trading.

We are all short volatility

The conceptual framework for thinking about volatility described above is, arguably, universal and independent of market regime. In order to link the framework to the current regime, we need to introduce one more concept. Enter the notion of the synthetic short volatility position carried by most investors.

The logic is simple.

Alpha creation in for most strategies can be decomposed into two drivers in the form of asset (eg stock or sector rotation) selection and being short volatility. The relative weight between these two factors depends on overall asset correlation. When intra-asset and inter-asset correlation is low alpha generation will tend to be driven by asset selection. As correlation increases, the source of alpha creation collapses into a synthetic short volatility position.

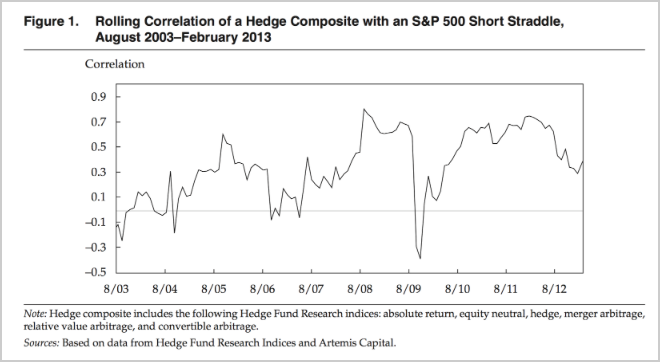

The following chart provides powerful support for this argument. Indeed, across market regimes most active managers’ return remain substantially correlated to a short S&P volatility position,

Source: Christopher Cole, April 2014

This is a crucial insight in my view and highlights two important points.

Firstly, it ties a nice ribbon on the argument above. The relationship implied by the chart suggests that no matter the particulars of a given active manager’s strategy, it will tend to be positively correlated to a short volatility position. If you accept this proposition it also becomes clear that most active managers would benefit from having a framework to manage this synthetically short exposure. Remember, that this is not merely about naively hedging out your implied short volatility position, but by exposing yourself to volatility (long and short) using a deliberate and dynamic strategy [3].

Secondly, it provides an important perspective on the current market regime characterised, as it were, by the hunt for yield and investors' (reluctant) stretch for long risk asset exposure. Quite simply, it is my contention that aggressive central bank intervention has exacerbated the market’s synthetic short volatility position and forced investors to double up on this already embedded position. This is a key point for Cole too;

Amateur traders are enjoying the Fed-induced liquidity spree by shorting volatility through ETPs, and they all believe they are geniuses for doing it, but in actuality they are more like the shoeshine boy of the past.

The current situation feels a lot like a carry trade on hyper speed to me. Investors are picking up dimes in front of the proverbial steamroller. However, contrary to plain vanilla carry trades (e.g. in FX markets) there is currently an almost diabolical element of reflexivity present. Central banks have been tasked with the job of making sure that the integrity of the financial system remains sound. They solved this task admirably during the depth of the crisis in 2008, but in the context of traditional central bank goals of price stability, employment and growth crisis measures are poor conduits. Indeed, it is increasingly clear in my view that such policies used to achieve traditional central banking objectives are likely sowing the seeds for the next crisis. As I noted above, this has all the elements of a Faustian deal and investors are being forced to take it.

The hunt for yield and new tail risks

Putting a name on unknown unknowns is impossible by definition, but the unravelling of the great hunt for yield could conceivably be argued to fall into this category in my view. It is famously said that there aren’t supposed to be any free lunches for investors, but this tried and tested meme has not been entirely accurate in the past 3-5 years. Consequently stocks and bonds have appreciated together in the vacuum of missing assets left behind by central banks’ policies.

We have seen a slight reversal of this in the past 6 months, but investors should take note of what happened during the initial tapering fright in the spring of 2013. US 10y yields moved higher and the S&P 500 sold off. It is difficult to imagine a more frightening price action than this. I remember a meeting with a long/short fund manager in May 2013 desperately asking me what the heck he should buy. He had been long bonds and had even timed it appropriately relative to the sell-off in equities, but to no avail. Needless to say, it was difficult for me to provide him with an appropriate answer. After all, telling an investor to buy volatility after the fact is of little use.

According to the rules of modern portfolio theory (MPT) as expounded by Markowitz this is not supposed to happen (or at least not that often). It should also then be clear that in a world where stocks and bonds are uncorrelated a long bond position serves as a proxy for a long volatility position. Indeed, in the current climate, the trade, for those who are adamant that we are in the final stages of an equity bubble, is easy. They should buy the US 10y note. If the US stock market were to collapse there is no way that the yield curve could stay as steep as is currently the case. US 10y yields would fall to reflect lower future growth prospects. The yield curve would bull-flatten with short rates pinned to floor and long rates falling on the back of a drop in risk assets. In the alternative scenario where the Fed hiked prematurely the yield curve would likely invert, but the result would be the same. Short rates would rally rapidly, long end rates would fall and the economy would likely fall into a recession. In many ways, such a catalyst for a recession and adverse stock market reaction would be a text-book case.

But it may not be that easy. Cole presents perhaps the most important point of his entire piece;

An interesting and perhaps inconvenient truth for MPT is that bond prices do not always move in the opposite direction of stock prices. MPT has been built on the basis of anti-correlation between bonds and stocks. But is there a risk of a paradigm shift? Recall the concept of the impossible object. Is it possible to enter into an environment where stocks and bonds collapse together? (…) If stocks and bonds decline together, investors will definitely want to own volatility.

This point neatly brings us full circle in so far as the imperative for trading volatility goes. Personally, I think that the risk of a sustained period where stocks and bonds decline together represent a major risk for investors. This would be particularly true if it occurred in the context of one or more central banks losing control over their reaction function and their policies. Remember here that while any central bank conceivably could always and everywhere steady the ship (eventually), the perception of rudderless central banks would be dangerous.

Another catalyst here in my view would be a hiccup in China, which drastically changed the flow of funds dynamics and forced China into a selling position of its FX reserves.

All this then is to simply say that investors should think about their volatility exposure. This may seem a disappointing dividend for wading through this essay, but sometimes the simplest messages are also the strongest. As a final note and before you sharpen your pen to write me a nasty gram. No, I am not on Mr Cole’s payroll. I endorse his conceptual views but not his product. In fact, outsourcing your volatility exposure may not be an appropriate strategy at all. Finally, this essay has been short of concrete advice so let me end with one. Every investor should know her realised 12m correlation to a short straddle position on her benchmark equity (or credit) index. Once you have this information you are one step closer to a fully-fledged volatility exposure strategy.

--

[1] – The narrative laid out by Cole is not a new one for him or Artemis Capital Management. I first came across it in this presentation from March 2013. The updated CFA article linked above however is the most concise and updated version of the argument though.

[2] – After all, such a strategy is likely to be the raison d’etre for the business and he is unlikely to give much details away. If you want exposure to Artemis Capital Management’s specific volatility strategy, you will have to invest in Mr Cole’s funds.

[3] – This is deliberately vague. However, the point of thinking about volatility as a term structure stands. If the volatility curve is steep relative to its history you would put on a flattening strategy (for example buying short term volatility and selling long term volatility). This actual strategy employed is essential a question best answered with an empirical model.